An Insatiable Quest for Brazilian Music

by François Pachet

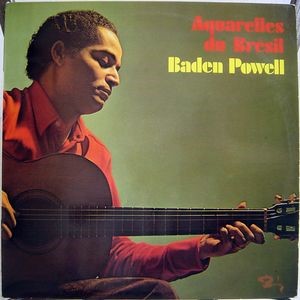

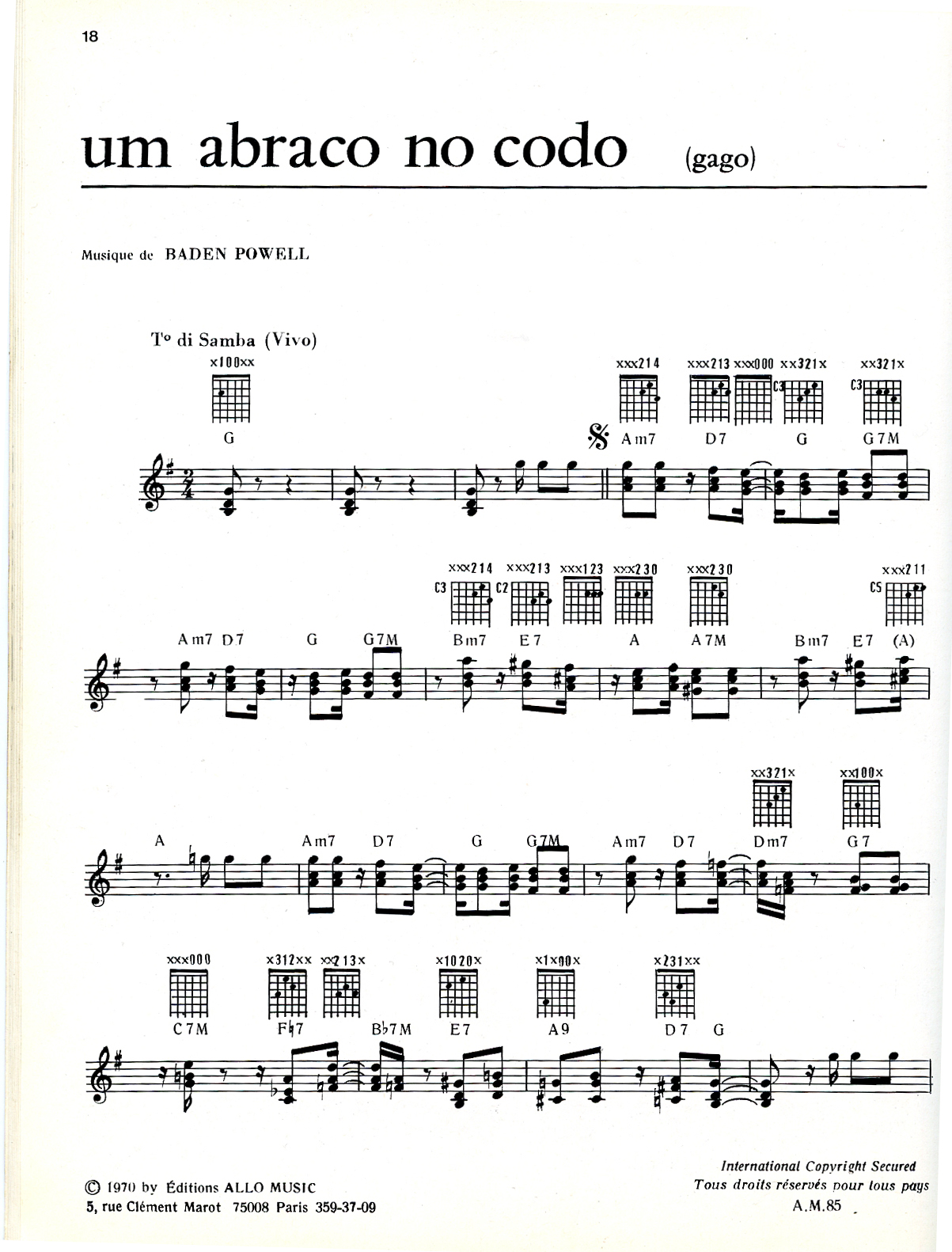

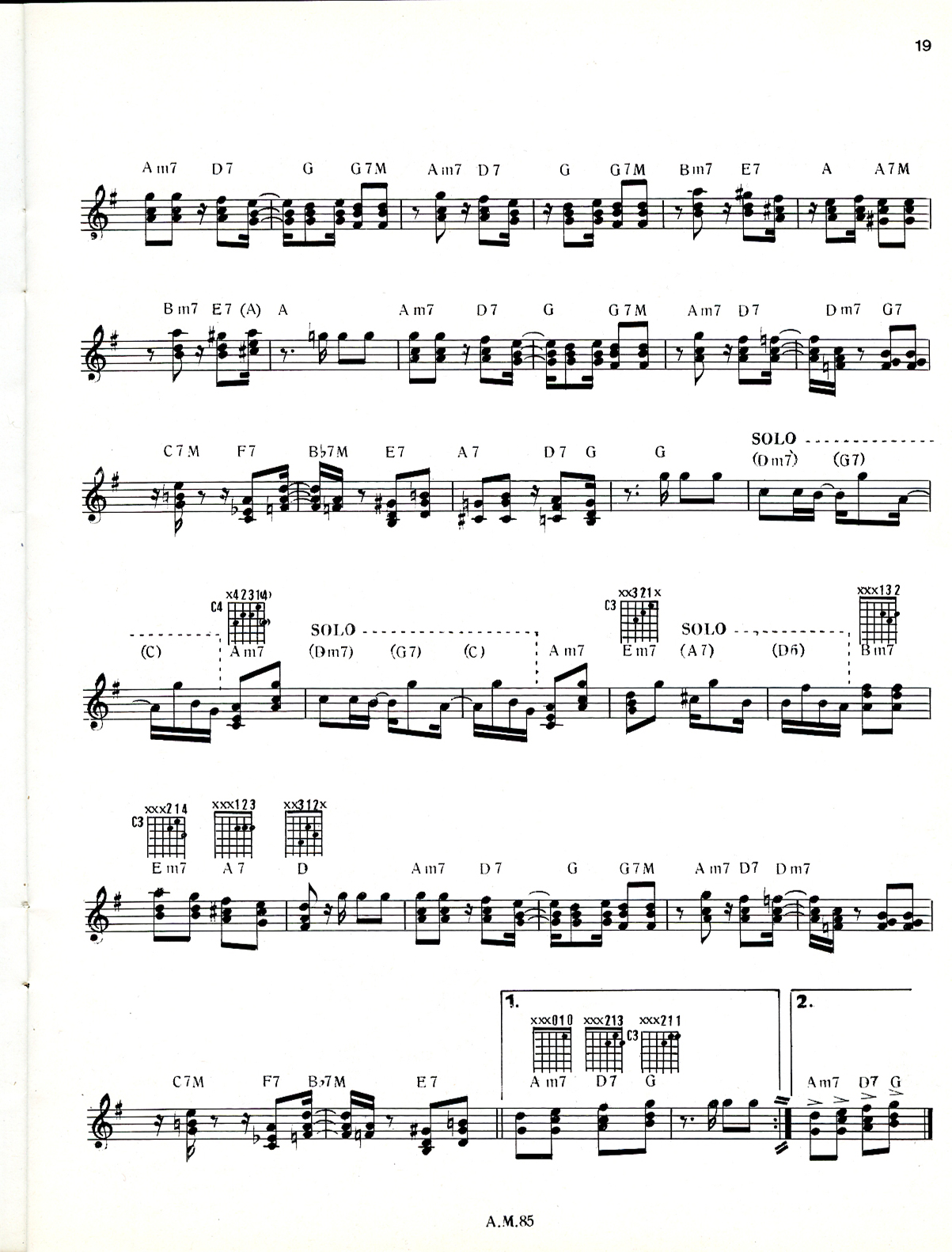

It started with the record Aquarelles du Brésil by Baden Powell, published in the French label Barclay in the 70s. I listened to this record extensively when I was 10 or so in the hills of Meudon. Several songs in this record captured my attention for years. Abraço no Codó fascinating by the fast accompaniment and the chord voicings which I could not figure out how to play right: I got the harmony more or less, but not exactly as it was played. Same for Iemanja, a song about the Africa-born Brazilian deity of the sea, and the fascinating texture created by unorthodox 8-note arpeggios.

In Meudon, I was learning classical guitar with Roland Dyens - I was one of his first students - who just came back from Brazil where he had discovered with great enthusiasm Bossa nova and many news ways of playing guitar, which he taught with passion to his students in France over the years. I followed him when he was appointed at Ecole Normale de Musique. Between the practice of Villa-Lobos and Fernando Sor (Dyens was known notably at that time for his interpretation of Villa-Lobos' concerto for guitar and small orchestra), he taught us the basic chords, and rhythmic cells of Bossa nova. I remember students practicing Bossa in the austere corridors of the school, not quite the usual repertoire for this venerable institution. We were secretly fascinated by this guitar idiom, which opened new doors with the instrument. We did not know it was possible to produce these beautiful harmonies and groovy rhythms with a guitar! He disclosed these magical chord progressions on small pieces of yellow paper I still have somewhere. According to him, there were three basic songs to know: Manhã de carnival, Samba de Orfeu and A Felicidade: the 3 main songs of Orfeu Negro, the famous 1959 movie by Marcel Camus. He was also improvising songs all the time. While I was listening and watching him play I tried, usually in vain, to remember the fingerings of these fascinating chords. When I was back home I could remember only a fraction of what he had played: this is how the quest began.

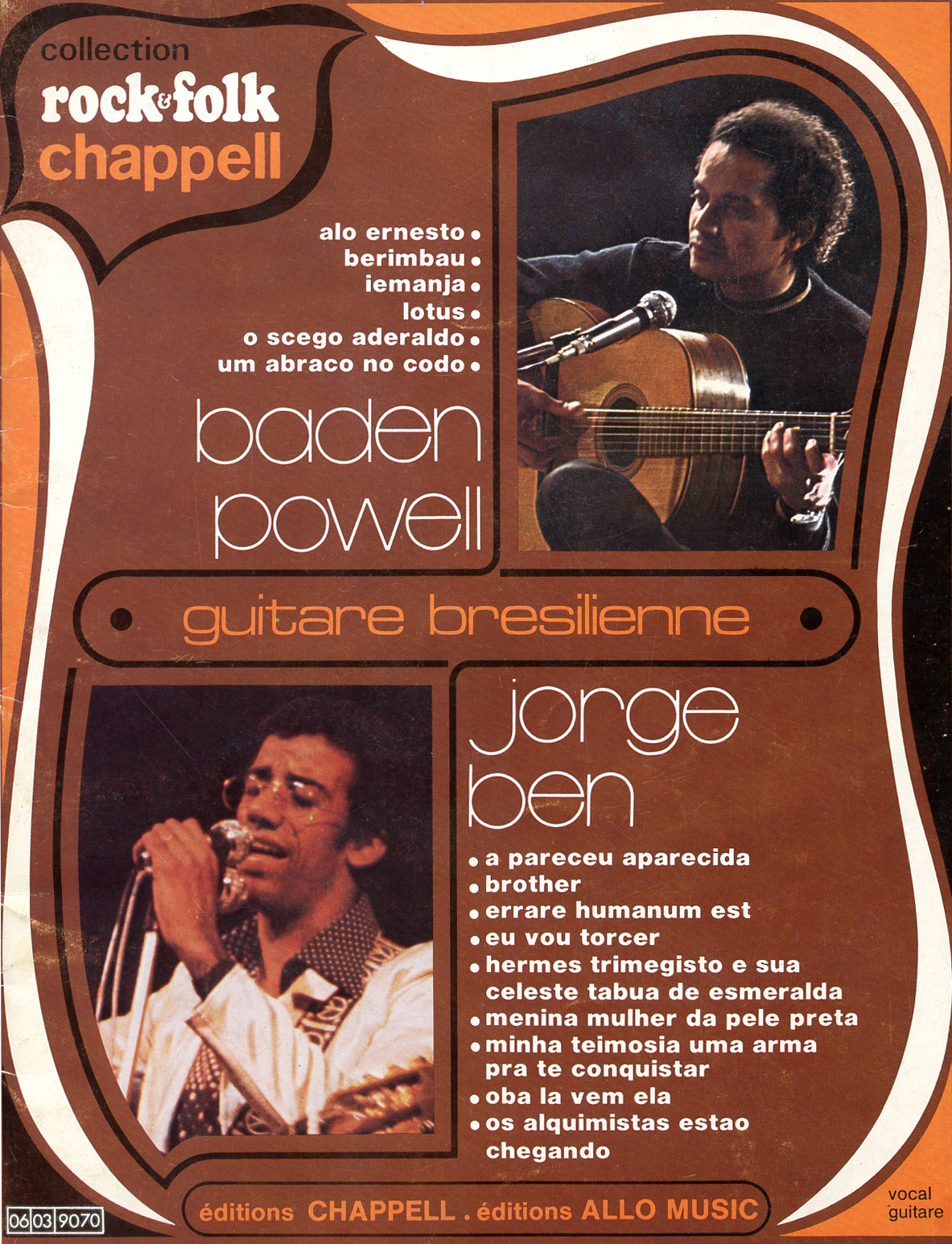

Even with these precious information and lessons, I still could not play Iemanja or Um abraço no Codó quite right. I looked for scores and transcriptions, but at that time they were rare; Brazilian music was not as widely known and disseminated as it is today. I once found a rare and improbable score at the Pasdeloup music store (boulevard Saint Michel) in 1979 or so: a songbook of Baden Powell which included Iemanja and Um abraço no Codó, it said on the cover! Unfortunately the score had nothing to do with my beautiful recording…

15 years later, when I was finishing my PhD in 1992, Geber Ramalho came to my lab (Laforia, now Lip6 at UPMC) to start a PhD on music creativity and modeling. We exchanged a lot, for the first time in my life I could talk about guitar to a real Brazilian guitarist, who was, like me, also a computer scientist. After his PhD, Geber came back to Recife where he got a position at UFPE and continued working on musical informatics and modeling of Brazilian guitar among many other things.

Geber's visit to UPMC had a lot of impact, and initiated a continuing stream of exchanges between Paris and Recife. Many Brazilian students came in his wake to Paris, notably Giordano Cabral, who did a PhD at LIP6 on automatic harmonization, supervised by Jean-Pierre Briot and myself. Others ones such as Sergio Queiroz (now at UFPE), Charles Madeira (now at UFRN), Aydano Machado (now at UFAL) or Hendrik Macedo, (now at UF Sergipe). Several French researchers were also caught in this exciting and friendly thread, such as Vincent Corruble and Jean-Daniel Zucker, and this community is still active today.

My first visit to Brazil was only in 1999, thanks to an invitation by Geber to do an invited talk to the SBCM conference (held by the Brazilian Computer Music Association) in Rio. When I visited the Pão de Açúcar, I had the images of Orfeu Negro (Morro de Babilônia especially) in my head, and kept trying to superimpose them on whatever I saw. Things had changed, obviously, but Bossa nova was still there, present everywhere. Jobim was dead but he had an airport in his name… I came back several times to Brazil, notably for Porto Musical (2007, 2011), as well as for several workshops organized by our mutual friend Jean-Pierre Briot, then head of CNRS-Brazil, notably a workshop on interactive music in 2009 , held in Recife and Rio.

In 2007, Sergio Krakowski, a pandeiro player, who was doing a PhD at Impa (Rio) spent 1 year at Sony CSL with my team to work on augmentations of the pandeiro for interactive performance. This work led to several publications and concerts (Siggraph 2009). Sergio now pursues a successful international musical career.

In 2013, inspired by the frustration of seeing computer music research essentially technologically-driven and too often musically ungrounded, I started a series of tutorials targeted at researchers in music information retrieval, to talk about the specifics of each musical style, and highlight “what is interesting” in a given musical style. I did a first tutorial of this kind about jazz (see Ismir 2012 and the video recording on Youtube). Motivated by the positive reaction of attendants, I did one the next year about ... Brazilian guitar, with Giordano Cabral. This tutorial was presented twice (in Brazilia for SBCM 2013 and then Curitiba for ISMIR 2013) with some success. The series has continued and tutorials of this kind are now held regularly at each Ismir conference. Preparing and giving this tutorial was a unique opportunity to reflect on Brazilian music, to sort out ideas and knowledge but also to discover many other styles and Brazilian guitarists: the best way to learn something is to teach it!

While I was searching for documentations for the preparation of the tutorial, I found a video of an interpretation of Abraço no Codó. The explanation I had been looking for many years was there! The chord I was trying desperately to play right was played in a different way than what I thought (first inversion), and with this voicing the whole song became obvious and simple. At the same time, Giordano proposed to include in our tutorial some examples from Edu Lobo’s guitar style (Ponteio). These arpeggios were very similar to the ones Baden Powell played in Iemanja: the loop was closed?

Not quite.

Before this trip to Curitiba, I also had the opportunity to meet and discuss in length with Ivan Lins, the famous composer (Começar de novo among many other) at Jean-Pierre's house in Rio, and this was a fantastic moment. He explained to us the roots of his unique composition and accompaniment style. For instance, he explained how his characteristic comping style on the piano was born out of the fact that when he was a child, his parents had bought him a detuned piano: when he transcribed the songs he heard on the radio, he had to play them a semi-tone higher, forcing him to acquire rare skills with non-conventional chord keys and fingerings. I was also happy to see that my quest for understanding the mysteries of Brazilian chords and harmonies was shared by many Brazilian musicians.

These activities and interest for Brazilian music pushed me to apply for a PVE grant (Pesquisador Visitante Especial) from Capes to study more in depth the musical styles of Brazil. I obtained the grant in 2014, to work with the energetic and inventive Mustic research group, led by Geber and Giordano at UFPE.

During our first two visits to Recife we recorded several guitarists, notably during Porto Musical 2015 at PortoMídia, the new technological hub of Recife Antigo. We experimented with our techniques for style capture and generation, and this created a lot of enthusiasm with our Brazilian colleagues. We now have a plan to collect all, or at least a substantial part of, the rhythms (so-called levadas) of Brazilian music: the quest for the understanding of Brazilian music is only beginning.

François Pachet

Epilogue:

• Clodoaldo Brito Codó, to whom the song Um abraço no Codó is dedicated composed the song Um abraço no Baden in response.

• Pierre Barouh must be thanked here for having brought Bossa nova to France early on. He described himself rightfully as “le Français le plus Brésilien de France” (the most Brazilian of the French people) in his translation of the song Samba da bençao (by Baden Powell and Vinicius de Moraes) sung in the 1966 movie Un homme et une femme by Claude Lelouch. During his trips to Brazil he recorded unique footage of Brazilian musicians, available in his documentary Saravah, including a touching interview of Baden Powell about Iemanja and the African roots of Brazilian music. Note that in this interview Baden plays another version of Iemanja than the one on the album mentioned above.